copyright assistance

YouTube and the copyright system

YouTube and the copyright system

YouTube and the copyright system

Remember when YouTube's entire business-model relied upon (what appeared to be) profiting from copyright violations? Back in 2006? How did they overcome that?

ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC

YouTube and the copyright system

YouTube and the copyright system

Are you a music publisher? Or want to be? You should at least know what ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC are, and how they work.

File for Copyright yourself!

YouTube and the copyright system

File for Copyright yourself!

You can file for copyright yourself, and the fee might be as low as $35. You can do so at copyright.gov. Be aware, the user-interface is a bit strange.

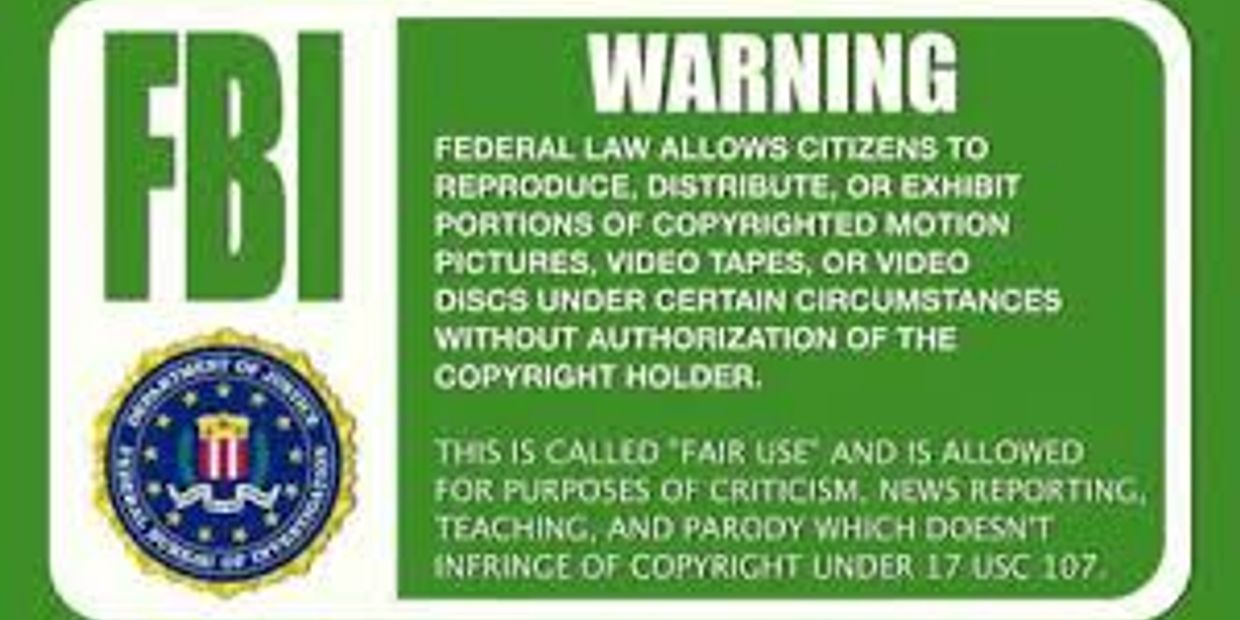

explanation of "Fair Use"

Cover Bands (Tribute Bands) and "Fair Use"

File for Copyright yourself!

The doctrine of "Fair Use" is one of the most misunderstood and misinterpreted legal doctrines ever! Its probably not what you think!

Cover Bands (Tribute Bands) and "Fair Use"

Cover Bands (Tribute Bands) and "Fair Use"

Cover Bands (Tribute Bands) and "Fair Use"

Does being in a Cover Band (or Tribute Band) put you at risk of copyright violation? Why or why not?

Tattoos and Copyright/Trademark

Cover Bands (Tribute Bands) and "Fair Use"

Cover Bands (Tribute Bands) and "Fair Use"

Copyrights are difficult to understand, but tattoo images took this to a whole new level of confusion. Its not just enforcement problems, but also determining who is the infringing actor.

YouTube and Copyright

Historical perspective to help us understand's today's YouTube.

We have gotten to the point that the US Government and federal courts are unable to properly police our copyright system. Further, certain aspects of our copyright laws are antiquated, some going back to the 1860's, and do not properly address changes in technology and technology culture. In short, our copyright laws were made for a different time.

This is important for musicians, people in the music-related industries.

Still, because there is so much money and commerce involved, what we are seeing is private companies stepping in to filling the void normally occupied by the government and the federal courts. An example of such a private actor is Jeff Price, and his various companies Audiam.com and previously, tunecore.com. There are many other examples, including YouTube.

BACKGROUND\CONTEXT

To best explain this issue, its useful to look backwards into how YouTube came into existence, and how a large private company (Google) more or less forced a very large change in copyright enforcement, with the US Government welcoming the assistance.

Long ago, before YouTube was acquired by Google, it was predicted that YouTube could not remain a viable business entity because. A key principle that made (early) YouTube attractive to users was its skirting of copyright laws. People could and did post copyrighted content on YouTube, and often suffered nary a penalty. These people, and YouTube, often “piggybacked” on and profited from someone else’s creative efforts.

An early example of this was illustrated when Viacom sued Google over alleged copyright violations. This lawsuit was filed in 2007, but not settled until 2014. At one point Viacom, had been seeking $1 billion in damages from Google. However, no money traded hands in the settlement.

In 2007, the copyright lawsuit looked like it would have major implications for the way the Web worked. As a patent/copyright/trademark attorney, I remember thinking this myself! “OK, that’s the end of that fun”, etc. But by 2014 the core issues have been settled by both the Federal Courts, and the marketplace, specifically YouTube’s skillful innovation of a ContentID tag.

Like many other media companies, Viacom had originally objected to the fact that lots of its content appeared on YouTube without permission. But Google, which acquired YouTube in 2006, has more or less made peace with most big content companies, in part using a “ContentID” system that allows copyright owners to track their stuff on the world’s largest video site.

The system also gives content owners the ability to demand “takedowns” of their stuff — or the option to run ads against it. That is, when a content owner discovers a violation, they can reach the party who posted the material, ask them to run an ad, and both parties can benefit. No “Takedown” occurs, and the situation does not need to be adversarial.

In fact, many providers of e.g. background music, beat tracks, or other support material, now hope that someone is using their material and violating their copyright. With an easy negotiation semi-brokered by Google, each copyright violation can (eventually) mean more money in the pocket! Without using the federal courts. Without using an attorney (which we love)!

In this sense, in a lot of important ways, Google is acting as a de-facto Court system, but hugely more efficient and more marketplace-centric. Amazon is also doing something like this for Trademarks, doing important work that the Federal Courts simply cannot get to. This will be the subject of a separate article, too difficult to briefly explain here.

This is an amicable solution in which all parties profit, and people stay out of the Federal Courts. As an attorney who does not like other attorneys, I prefer this system. This arrangement has also enabled companies to step in to help Google "police the Internet" of copyright violations, and protect content providers, musicians, and other parties in the music-related industries. As stated, examples include are companies like Audiam.com and tunecore.com

These companies take YouTube’s ContentID system referred to above, and add to it. They also protect people against false Takedown notices by YouTube. Unfortunately, YouTube sometimes notifies (apparent) violators they are posting copyrighted materials which are in breach of YouTube's user agreements, even when they are the creators and owners of that material.

This is an example of harnessing Google’s creativity and inspiration to build the regulatory systems of the digital age, rewarding for-profit and nonprofit innovators who can come up with better regulatory tools.

PERSONAL OPINION\EDITORIAL

It is my position, as a patent/trademark/copyright attorney, that the present solution is better for users, viewers, content providers, and even large media companies. Although there are still abuses, leaving the federal Courts to resolve this alone, by themselves would not have worked. Further, while YouTube’s beginnings may have been built on copyright violations, YouTube is now the #1 music destination site on the planet for music discovery and search. Further, YouTube also enables and facilitates the end-customer not just listening to music, but also “using” that music in various contexts that in some ways benefit the original artist.

This editorial is coming from someone who worked as an attorney in the Department of Commerce, and saw what happens when the Federal Government and Courts are the sole parties responsible for resolving complex intellectual property disputes, including small businesses with limited budgets. The result was often a big mess.

There are things the federal government and courts are good at, and things it shouldn’t be doing, and can’t do.

CONCLUSION

Digital services like YouTube, and everyone else that distributes lots of content uploaded by its users are not responsible for copyright violations if they don’t explicitly encourage them, and if they let copyright holders take down stuff they don’t want up there. These services are not "publishers" in the traditional sense of the word, and cannot be expected to self-police all the content that is posted. Its hard to clearly define what they are, and they certainly bear a resemblance to publishers. But what we want to avoid is putting them in a position of having to police content (using the word “police” as a verb). These mechanism are not like a newspaper or magazine, where there is a finite set of writers and photographers, a finite amount of space, and a completed, finished document that can be reviewed prior to publication.

Again, if someone has worked with Jeff Price, or one of his companies, we encourage you to contact us here.

ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC

Very few artists truly understand what these organizations actually do

One good thing about the modern music industry is there are many ways to be heard. Self-management has never been more accessible to a typical composer than in 2018 and beyond.

Unfortunately, many musicians and composers neglect this important principle. Also, the music industry is full of quacks, cons, scams, and kooks. There is no shortage of ways to get cheated and conned.

To address this, you songwriters and performers reading this blog should consider joining a Performing Rights Organization (PRO) such as but not limited to BMI¸ ACSAP, or SESAC. However, be aware, by no means is this the end of their ways of protecting your musical assets, but an important step nonetheless. Do not rely on an (alleged) manager to do this for you. You should research this yourself!

There are many different types of payment rights, but one of the most important is a performance right. The payment corresponding with that performance right is known as a performance royalty. Any time one’s music is played on the radio (terrestrial, satellite, and internet), in stores, on TV shows, broadcast on the radio (terrestrial or satellite), used on TV or movies (including commercials), performed or streamed live (like in bars, restaurants, performance venues), streamed over digital services (such as Spotify or Pandora) films, video games, and in presentations, or performed by someone else in a live venue — you are owed a performance royalty. Ostensibly. But that does not mean you will ever receive that payment.

PRO’s will collect these royalties for you. That’s why upon joining, they ask you for your bank account information. This is not to cheat you or take your money. It is so they can figure out where to put the money they dig up for you. Money that you likely never would have found for yourself.

Whether songwriters and performers realize it or not, these PROs are important, and can do things for you which it would be very difficult for you to do yourself. But, people tend to neglect this because it’s a dull, geeky, non-glamorous part of the music industry. Boring and tedious.

The PRO will ensure all venues have a license to play music, collect public performance royalties from all, track who hasn’t paid up, and then determine the composer, publisher, and songwriter to pay for each instance. This is a lot of work. The PRO’s have the ability to find out when a composer’s music gets played, using extensive resources far too complex to explain here.

The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) is a not-for-profit organization. It represents more than 10 million works from over 550,000 members. ASCAP membership is $50 for both songwriters and publishers. ASCAP’s total cash distribution for 2016 is estimated to be $918 million. Most readers of the blog have probably heard of ASCAP. ASCAP’s membership size is estimated at 660,000 members, including Justin Timberlake, Vampire Weekend, Duke Ellington, Dave Matthews, Stevie Wonder, Beyonce, Marc Anthony

BMI has two different styles of membership, songwriters and publishers. Songwriters can join for free, but must sign up for 2 years, and must provide a valid bank account. Publishers pay between $150-$250, and must sign up for 5 years.

BMI’s Membership size unclear, but at one time included Lady Gaga, Taylor Swift, Eminem, Rihanna, Maroon 5, Dolly Parton, Shakira, and Green Day. BMI’s total cash distribution for 2016 is estimated to be $931 million.

SESAC serves around 400,000 musical works from over 30,000 affiliated writers. SESAC is invitation-only. In writing this article, I had more difficulty getting cost and revenue information about SESAC. SESAC membership is estimated at 30,000 members, including Bob Dylan, Neil Diamond, Young Love, Rapture, Adele. There is a rumor that Mariah Cary quit BMI to join SESAC.

PROs also tackle other issues impacting their members, such as fighting music piracy and keeping up with changes to the industry that have resulted from the advent of digital music. I believe that it’s important for songwriters to learn about the PROs.

Next, do not mistake a music publisher for a PRO. These are different. It is also this author’s belief that you should be your own publisher. Remember also that there are other types of musical rights that can be monetized. One example is “mechanical rights”. However, a full discussion of this would be beyond the scope of this blog, and even if not, is dull and tedious. The typical right that is most often neglected, and most misunderstood, as the performing right. That is why performing rights were chosen for this article.

On a final note, in researching this article, I watched numerous YouTube videos using the search terms “ASCAP v. BMI”, “ACAP v. SESAC”, and others. While there was plenty of rubbish to filter through, and lots of foul language, in the end I noted some pretty solid insights. One example is from songwriters and publishers who are actually making money in this industry (rare), and have quit one PRO and joined another. I found their remarks less biased, more accurate, and less doctrinal and didactic than answers I have received from other IP attorneys. Again, as is often the case, on some legal-commercial issues, I find that someone who has been in an industry, who has participated in it, often has a better and more accurate perspective than an IP attorney. Often, IP attorneys only see when things go wrong, the disputes, the lawsuits, etc.

HOW TO FILE FOR COPYRIGHT

The filing process

SUMMARY OF THIS ARTICLE

1) Have any of you ever filed for copyright yourself? It’s a considerable hassle.

2) Even if you have someone else performing this service on your behalf, you should still be aware of how it works.

3) If you are relying on mere “common law” copyright protection, not filing for Federal Registration at all, you may regret that. The U.S. Federal copyright system is accessible to a lay-person, an attorney is not always needed. The filing fee may be as low as $35.

4) In the event you have actual copyrights Registered, it’s important to make it very clear who owns them. Neglecting this can harm you.

This article will illustrate the above points.

First, for anyone who wants to file their own copyright, they need to visit copyright.gov. Even if they hire an attorney or other service provider, everyone files at the same place: copyright.gov. Why hire an attorney to do what you can do yourselves?

Next, it’s important to understand the difference between a common law copyright and a Federally Registered copyright. These are different, with different legal implications. A “common law” copyright comes into existence at the moment an artist or creator renders their creation into a fixed, tangible medium of expression. No Federal Registration is required to say “I have a copyright”. For example, I saved this article (more like a blog-post) on my computer, and when I hit “save”, a “common law” copyright came into existence.

A Federal Registration of a copyright is different, and requires more work. The starting point for everybody is copyright.gov, shown below.

The copyright.gov site offers at least 3 options, “Register”, “Record”, and “Research”. This article will discuss only “Register” and “Record”.

To Register, one hits the “Register” button. That will bring up a confusing GUI, with choices where artists and creators can make all kinds of interesting mistakes.

It can be very difficult to decide which category your specific artistic work falls into. Because this blog is music-related, an important choice for you readers might be whether a song is an example “Performing Arts”, or whether it is “Digital Content”. Another potential area of overlap is whether something is a “Photographs”, or other form of “Visual Arts”. It could be both.

Suffice to say, when in doubt, try filing across multiple categories.

Finally, lets say you already have copyrights Federally Registered, in whatever category. But now let’s say these copyrights are worth money and you are trying to sell them. In that position you should be familiar with the below, specifically the “Record a Document” option.

This “Record a Document” section is similar to Recording of Property Deeds. For anyone selling their house (a “tangible” property), they know that they buyer wants to make sure that the seller actually owns the house in question. One way to check this is to check a local Registrar of Deeds. Copyrights are similar, except they are “intellectual” (not tangible) property. Either way, the buyer wants to be assured that when they give their money, in return they are given authentic rights in a property. Recording documents related to your copyrights are one way to achieve this. The buyer can look up your copyrights and have some assurance you really have rights to sell or license these properties.

TAKE-AWAYS FROM THIS ARTICLE

Don’t ignore the US copyright system, be aware of at last some aspects of how it works. Its in your self-interest to do so. Further, all copyrights flow through exactly and only one place, and that is copyright.gov.

No need to rely on this website, everything herein can be verified by going directly to copyright.gov. That is what any attorney would do anyway, so why not see it for yourself.

explanation of "Fair Use"

Additional Information

This article is coming soon, but is not yet completed.

COVER BANDS AND COPYRIGHT

Hopefully Good News for Aspiring Musicians

TRIBUTE BANDS: A PRO-TRIBUTE EDITORIAL (HOW THE LAW WORKS)

INTRODUCTION

Tribute bands make an lot of business sense, although they certainly skirt the boundaries of copyright and trademark law. These two legal areas overlap, but still have a lot of differences. In either case, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but is it infringement? One would think that tribute bands would have to seek approval directly from the original artists and pay for the use of their songs. This is not the case.

The current music licensing system is designed more for cover bands, which generally tend to perform on a much lesser scale than tribute bands and vary the songs they perform. As such, tribute bands kind of “fall through the cracks” in copyright law (of which there are plenty). But is anyone really harmed? How much of that revenue truly belongs to the original creator?

COVER BANDS v. TRIBUTE BANDS v. REVERENCE BANDS

Tribute bands do not perform original songs. Instead, they exclusively perform songs by the band they pay tribute to, usually mimicking the band’s appearance, style, and name, often at a fraction of the price. Many tribute acts are merely overzealous fans badly imitating their heroes, but some can actually make a living. A surprising number sell out major venues in cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles, and hire an agent.

There has been an increase in both tribute and cover bands that perform copyrighted music popularized by other bands. These bands exclusively perform copyrighted works of other artists, often paying little or nothing directly to the copyright holders. “Cover bands” perform a variety of popular artists’ songs, while “tribute bands” focus solely on one artist or creator. Tribute bands tend to perform on a larger scale than cover bands, some having both national and international success.

There exists another even more strange type of band, a “reverence band”. These nut-cases adopt the persona of the original artists through the use of costumes, make-up, stage dress and effects, and/or between-song patter that quotes the original artist.

REACTION OF ORIGINAL ARTISTS

The original artists vary in terms of their reactions to tribute bands, ranging from supportive to litigious. Some legal scholars suggest that tribute bands can and should negotiate directly with original artists for the use of their works. I disagree, and many prominent artists also disagree, among them Mick Jagger. However, Bon Jovi’s lawyer once sent a group called “Blonde Jovi” a cease and desist letter. Gail Zappa alleges that bands cannot play her late husband’s music up to par, and therefore they tarnish his image. She has been using legal threats in an attempt to discourage unauthorized performances of Frank Zappa’s music, accusing tribute bands of “identity theft”.

On the other side, many bands enjoy tributes, such as Elton John. Several of the remaining living members of Queen put together their own tribute band, the Queen Extravaganza. They are producers of the show, so they profit from this venture. Similarly, several other artists have blessed one tribute band as their official tribute band. For some famous artists, the motivation is to make sure a band playing their act keeps up the quality.

In other cases, the members of a tribute band are often more committed to getting the song right than the original artists. For example, the Rolling Stones are now so aged and decrepit that in their 2018 concerts, it is very apparent that they no can longer effectively play significant portions their music, and have become somewhat of a parody of themselves, a type of “karaoke band” that sounds, frankly, quite awful at times. They often slop their way through their most famous hits, merely approximating certain songs and often very clearly not even making an effort to get the song right, giving their tour the nickname “Steel Wheelchairs”. Meanwhile Rolling Stones tribute bands are often significantly more committed to getting the songs right and accurate.

TRIBUTE BANDS AS A WAY OF DEVELOPING ONE’S MUSICIANSHIP AND PROFESSIONALISM

Tribute bands vary widely in their rates of success. Some tribute bands are strictly local in nature, playing few performances for small crowds making little money. However, other tribute bands achieve both national and international success. As the name suggests, some tribute musicians love the original band. Others join because tribute bands represents dependable income in a difficult industry.

A good tribute band, however, has the potential to land in front of large audiences very quickly, which is a difficult threshold. Many musicians never reach this. After all, everyone already knows the music. They don’t need to create a fan base; they just need to prove they can satisfy the expectations of the huge, hungry fan base that already exists.

As will be discussed in more detail below, BMI and ASCAP provide what are known as “blanket” licenses, meaning that they automatically grant licenses to anyone willing to pay a standardized fee. This means there’s almost no barrier to starting a tribute band. Some tribute bands play bars that fit 200-1000 people as typical venues, also with corporate conferences and parties as staple tribute band business.

ASCAP/BMI/COMMERCE

Tribute bands are covered under the same licensing agreements as cover bands and other live musical performers. These performances do not infringe upon the rights of the copyright owner when done with permission. The three major performing rights organizations ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC, negotiate licenses for the use of copyrighted works and collect fees for the public performance of those works.

A common method used by these organizations are blanket licenses, which involve pooling and licensing of copyrighted items in a single package which allows the licensee to use any and all of the items in the package as often as they wish. Blanket licenses permit tribute bands to exploit an artist’s entire repertoire without having to directly compensate or seek permission from the original artists. Owners of venues where tribute bands perform are required only to purchase blanket licenses. Blanket licenses serve to limit the expense and difficulty of negotiating licenses with various copyright owners. ASCAP provides over one hundred different types of blanket licenses that vary in price, depending on the type of business seeking the license.

TRADEMARKS AND COPYRIGHTS

Tribute bands are often named after the original artist to whom they are “paying tribute”. Tribute band names are often a play on the original artist’s name, which are valuable federally Registered trademarks, using similar names such as “Blonde Jovi” and “Lez Zeppelin”. Most tribute band names are followed by the phrase “a tribute to [insert name of original artist here],” so that trademark confusion is reduced.

Interestingly “Fair Use” doctrine exists for both copyright and for trademark. However, the thresholds are very different. A question exists whether tribute bands are protected by fair use. The answer is “no, not really”, but also, “who cares”, and “almost no one ever attempts to litigate this, as it’s not worth it”. Trademark infringement is a federal case, which means expensive litigation. An original band would spend $150,000 or more for an injunction, the potential damages may not be that high, and stopping each tribute band requires a separate lawsuit. Threatening legal action is much cheaper. Occasionally such threats make tribute bands cease playing entirely. More often, they change their name or stop using the logo and keep playing.

STIGMA OF TRIBUTE BANDS

We shouldn’t look down on tribute bands. Performers like Sinatra almost exclusively sang songs written by others. Even symphony orchestras are tribute bands, they do Beethoven and Tchaikovsky covers. There is at least one website dedicated strictly to tribute bands, tributecity.com. There are numerous Justin Bieber tribute bands.

The lines between tribute band and original band can also blur. In 1995, singer Tim Owens went from lead singer of a Judas Priest tribute band to the lead singer of Judas Priest as he replaced its departed frontman. Mark Wahlberg starred in an awful movie about this strange event, called “Rock Star” (2001). Unfortunately, Marky Mark’s attempt at authentic singing in this movie was not much different from his fake bad singing in either “Boogie Nights” (1997) or “Ted” (2012).

Performers in tribute bands often straddle the border between professional musician and struggling artist. Musicians in popular tribute bands may hire an agent or producer (if they don’t already have one), they can expect fans to sing along at every concert, and they can tour full-time. On the other hand, they don’t get the full rock star treatment. The money can be good, although often not. Very elite tribute bands (of which there are few) might reach low six figures.

Tribute bands make economic sense. Most profits in the music industry are concentrated in the hands of a few lucky individuals. But they still can only perform in one venue at a time. Until bands start playing multiple locations at once (e.g. by cloning themselves), tribute bands are an obvious solution.

Further, tribute bands still allow plenty of room for creativity and entertainment musical expression and development. Additionally, no tribute band has ever refused to play its hit song, pissing off their audience. Meanwhile, many performers are very tired of playing their hits, and often refuse to play them or perform them poorly. For example, Kurt Cobain was famous for this with Nirvana, refusing to play “Smells like Teen Spirit”, and when the request was screamed enough times, spitting on his audience.

Tattoos and Copyright/trademark

Existing state of IP law is not set up to properly address the problems in this industry.

TATTOOS AND COPYRIGHT, TATTOOS AND TRADEMARK

SUMMARY

Anyone coming to this site is already familiar with tattoos. However, you may not realize that these are rotected by similar forms of Intellectual Property, copyright and trademark.

DEFINITIONS

There is no easy, short, concise definition for a Trademark. However, typically, a Trademark is a name, word, phrase, logo, symbol, design, image, or a combination of these elements that is intended to or is being used in commerce. Trademarks exist to exclusively identify a source or origin of goods or services.

As with trademarks, there is no short, concise definition of copyright. Copyright law seeks to protects original literary, artistic and other creative works of authorship. Copyrights protect the expression of an idea, but not the underlying idea itself. The expression of the idea must occur in a fixed, tangible medium of expression, and human skin is certainly an example of this. Copyright protection can apply to writing, art, music, dramatic works and other creative exercises.

Another form of Intellectual Property is Right of Personal Publicity (RoPP), which often used by celebrities to protect their image and likeness, not all of which can be protected by trademark or copyright. It is easy to confuse RoPP with Trademark, as these two have some overlap.

Trademarks exist to protect consumers, not sellers\creators, although sellers get an indirect benefit. Meanwhile, copyright exists to protect creators. This gives rise to a strange combination of protections which are not entirely compatible.

EXAMPLE TATTOO-IMAGES

If you remember nothing else from this blog post, remember this: a key factor in determining whether trademark problems exist is “likelihood of confusion”, as in “would a purchaser of the goods/service in this industry be confused over the origin/source of this product”.

In the cases of the tattoos of Snow White or Mickey Mouse shown above, the answer is likely “yes”. This is because these likenesses are instantly recognizable, and an average observer, even the reader of this article, might assume the tattoo arises from some type of implied license from Disney, thus Disney may be perceived as the “source” of the tattoo.

The same applies for tattoos of Taylor Swift and Garth Brooks. Further, such tattoos would also like be considered a violation of their Rights of Personal Publicity (RoPP), because it’s extremely likely the tattoo artist did not have their permission to use these images.

One factor encouraging tattoo artists to take these risks is that the fees for applying such specialized images may be quite a bit higher than their usual fees. Further, criminal law enforcement entities such as police and FBI in some ways gain an advantage by the proliferation of such highly recognizable tattoos, as their existence can make criminal suspects easier to identify. Also, especially for the larger tattoos, it is difficult for criminal suspects to get rid of them or cover them up.

Here is a problem that many artists and musicians are not aware of. If a trademark owner does not maintain quality control and adequate supervision in relation to the manufacture and provision of products or services, this could be considered "naked licensing" or “unsupervised licensing”. Such behavior could eventually harm the trademark owner's rights in the trademark.

The tattoos shown herein might also be described as “naked licensing”, but in a very diffused form. First, because some of the people shown herein, well, we would prefer to not think about them being naked.

But more importantly, because with the proliferation of Internet images, and with the proliferation and commercialization of tattoos, it’s easy to “lose control” of one’s image and artistic creations. This is true even though an image-owner may be diligently protecting their creations. As such, a presumption of a “naked license” is now more rebuttable than it used to be. No one, and no entity, not even China, can entirely control the Internet.

Accordingly, the burden on the brand-owner to protect their brand must be reasonable. Policing potentially-infringing tattoos is difficult. The existence of Facebook and Instagram make the enforcement process much harder, because the re-posting of photographs of the tattoos can transform one infringing use into something being seen by literally millions of eyeballs.

Policing Facebook and YouTube and sending “takedown notices” may not be effective. While some of these tattoos are truly awful, and could be said to be “tarnishing” the brand (e.g. McDonald’s, Taylor Swift), finding the responsible actor could be difficult. It is important to properly identify the various actors. The true infringer is not so much the wearer of the tattoo as much as the tattoo artist, although both are culpable. But its unlikely the Facebook or Instagram images of any particular tattoo will show where that tattoo was created. That brings us to our next section, remedies for infringement.

ENFORCEMENT

A Federally Registered trademark (symbolized by ®) grants numerous rights upon the registered owner, including the right to exclusive use of the mark in relation to the products or services for which it is registered. The owner of a Federally Registered trademark ® can prevent unauthorized use of the mark in commerce. Tattoos are big business and certainly commercial. The test for whether infringement exists is, most often, whether a consumer of the goods or services will be confused as to the identity of the source or origin. This is known as “likelihood of confusion”.

Infringement of a copyright occurs when someone displays a copyrighted piece without permission of the author, although many times the infringement is de-minimus and thus tolerated. A copyright owner must prove the copied work has a negative effect on the work's value or potential market.

On the other hand, the skin-wearer is less likely to be considered infringing, since his display of the work is usually not for profit and in most cases would not meaningfully affect the work's value or market. While numerous of the tattoos shown herein are indeed hideous, unpleasant, and poorly applied, the link or connection between the tattoo wearer and the holder of the commercial rights is extremely distant. The target of any enforcement action, whether copyright or trademark, would likely be the tattoo-artist not the tattoo-wearer, although both may be culpable.

What makes all of this hella-confusing is that some commercial images can be separately protected by both copyright and trademark, while other images may only be protected by one or the other, or perhaps have no protection at all. Further, copyright is not just one clear statute, but an often-misunderstood set of statutes and cases from which it can be difficult to determine boundaries.

REMEDIES

The extent to which a trademark owner may prevent unauthorized use of their trademarks depends on various factors such as whether the trademark is Federally Registered (symbolized by ®), the similarity of the marks involved, and whether the owner's trademark is well known or famous. McDonalds, Mickey Mouse are certainly well-known and famous. Also, Disney and McDonalds have money and are diligent about supervising use of their images and marks.

The means and legal rationale for protecting copyrights is very different from protecting trademarks. This is an extremely confusing area of law, in which even experienced IP attorneys can have difficulties. Some concepts are not protectable by copyright, some are not protectable by trademark, some may be protectable only by one or the other, and some may be protected by both.

The Disney images shown herein are based on copyrighted and trademarked Disney images, and are likely doubly-infringing usages. An errant tattoo artist is thus subjecting himself to “double-trouble“ legal liability, giving large entities like Disney, McDonalds, or Taylor Swift multiple ways to come after and Bust him.

As stated, it is usually not cost-effective for Disney to pursue legal action against the person wearing these images, awful as they are. Instead, the most effective mechanism might be to prevent tattoo artists from making further copies of these specific tattoo-patterns, but even that is very difficult.

The NFL also has some very valuable commercial images that they try to protect. These days, in 2019 and beyond, its easy to find NFL tattoos which are very likely to infringe the NFL’s copyrights and trademarks.

These tattoo-wearers may be surprised to find that the NFL is not amused by their intense (if not irrational) loyalty, but instead would like them to disclose the tattoo-artist that performed the work. Further, when teams like the Rams change cities, the tattoo-wearer may lose their sense of loyalty and then faces the formidable task of getting the tattoo removed or re-rendered.

Large companies with significant brand reputation at stake go to great lengths to protect their copyrighted and trademarked images, spend a lot of money, and, unfortunately, can be harsh and rough when they Bust somebody. One example of this is Disney, a company whose products are aimed at children, and as such those products are very vulnerable to misuse and misinterpretation. I chose Disney for examples because Disney has an extremely large budget and does not like their trademarks or copyrights violated or disparaged. I also chose Disney because of the numerous examples of disparaging and infringing tattoos that I was able to find. For some reason, people like tattoos that make fun of and disparage Disney and McDonalds characters.

A copyright owner must prove the copied work has a negative effect on the work's value or potential market. All the tattoos shown herein were chose because they are likely to be examples of tattoos which have the requisite “negative effect”, and thus subject to a claim of copyright infringement. However, measuring and quantifying that negative effect could be difficult.

As stated, the best target would be the tattoo artist, who is much more likely to repeat the offense and thus cause further harm. But if the tattoo-wearer will not tell you, or is not available, how can one determine who is applying these tattoos? One way is to look at the “sample book” that many tattoo parlors keep, showing examples of their previous work. But even this practice has limited effectiveness. People with specific tattoo requests often bring their own desired images to the tattoo artist.

Many NFL fans are very devoted to their favorite teams. Many have NFL tattoos, although these are likely a violation of both copyright and trademark law. However, these fans would likely not inform NFL attorneys which specific tattoo artist drew their tattoos unless they were compelled to do so. Further, the tattoo artists already know to be careful to not to include their NFL specimens in their sample books, but may still agree to apply NFL tattoos because the profits on such tattoos may be quite large, perhaps larger than their usual fees. They also may not be aware of the trademark implications of their actions.

COMPARISON OF TRADEMARKS AND COPYRIGHT

Copyright law is among the most difficult of all forms of IP to summarize, especially the enforcement aspects. Rather than try to lay out a framework, it may be easier to explain copyright by contrasting copyright with trademarks. While trademark law seeks to clarify source of products/services, copyright law generally seeks to protect original literary, artistic and other creative works, and is often oblivious to any particular commercial impact.

Additionally, while both trademarks and copyrights have been around for hundreds of years, they originated separately, evolved differently, cover different activities, have different rules, and raise different public policy issues.

Copyright law was designed to protect authorship and creative endeavors, and applies to the details of a work of authorship or art. Trademark law was not intended to promote business activity, but instead intended mainly to enable buyers to know what they are buying.

A trademark can be 'abandoned' or its registration can be cancelled or revoked if the mark is not continuously used. By comparison, copyrights do not go 'abandoned' merely because their owner stops using them in commerce. This is important from the standpoint of tattoos and tattoo artists, because copyright owners may not necessarily need to actively police their rights in order to make some kind of a stink. However, a failure to bring a timely trademark infringement suit or action against a known infringer may give the defendant a defense of implied consent or estoppel.

Accordingly, the trademark holders must be vigilant, “use it or lose it”, supervising their brand against even non-threatening usages, while copyright owners do not have the same duty. Thus, a tattoo artist may be more likely to hear from a trademark owner than a copyright owner, because of this affirmative duty. However, in either case, a big problem is how to supervise and prevent infringing mis-usages.

In summation, tattoos are an interesting form of intellectual property that is difficult to supervise, even though the commercial potential is enormous.

CONCLUSION

As tattoo art continues to grow and evolve and become a bigger part of our culture, the copyright and trademark laws and doctrine must evolve to keep pace with this trend. As stated, with the proliferation of Internet images, and tattoos, it’s easy to lose control of one’s image and artistic creations. At present, the copyright and trademark enforcement mechanisms are clumsy and misunderstood. Consequently, an aspiring musician, artist, or music-manager should try to stay abreast of these trends and be fully aware of how to protect their own image and likeness.

Learn More

We are trying to reach out to people in the tattoo industry. There is so much noise and confusion in this industry, that its hard to sort out what's what. SO, ask us, let us try to help you. No selling, just straight answers. No selling, just information.

If we don't know, and we are guessing, we will say so.